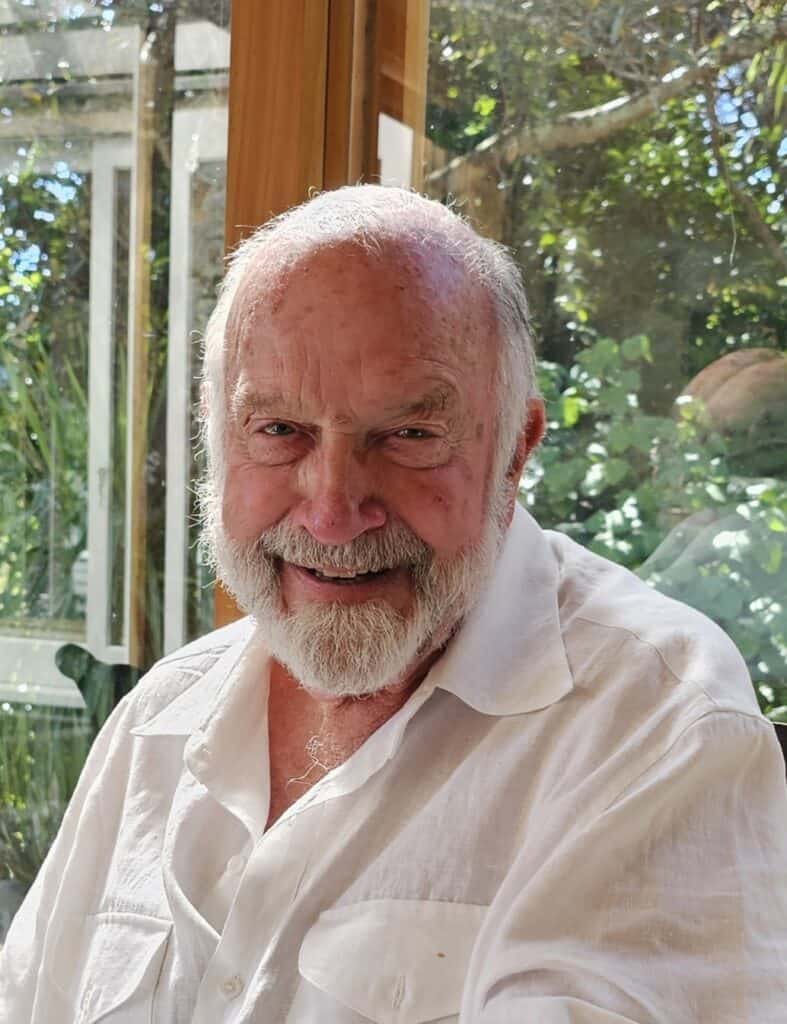

Professor Jim Wright was one of the early recipients of funding from the Whau Mental Health Research Foundation. Over the course of his career, with support from the Foundation and other groups he developed a sophisticated mathematical model of brain function that describes how information processing associated with cognitive function develops, how visual perception occurs and most recently how his work links with other current models of brain function that themselves link back to the abnormalities in brain function associated with mental health conditions such as schizophrenia.

How did the Whau Foundation support your research?

The Foundation played a crucial role in my career at several critical points. To explain how important its support has been, I’ll have to describe my rather long career, throughout which I have been dependent on research funding. This went from rags to riches and back again several times, and was saved by the Foundation when otherwise it would have lost momentum and dissolved, for sheer lack of funds. My case illustrates a more general problem. It is well known that researchers in New Zealand face limitations of budget compared to those in richer countries – but there is another challenge that seems less recognised. The smaller number of sources to whom one can turn when a line of work falls foul of other, unsympathetic, committees bedevils long-term work aimed at long-term outcomes. It is right that dead wood be cut out, but sometimes the presumption of death is premature. Mine has been a case in point.

Could you share a summary of your research project and what inspired you to pursue it?

As a young doctor entranced with the prospect of a career in psychiatry I believed that psychiatry should be based on an understanding of the function of the brain. Since this didn’t seem to be the case, with the confidence of youth, I thought I would see if I could help sort this out. I joined an international research effort labelled “Brain Dynamics”. Its object is to determine the rules by which the brain performs its most essential function – the embodiment of a thinking and feeling self. In 1971 I had the great good fortune to receive a research fellowship at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) – unusual for a medical graduate, but enabling me to work with the neurobiologist and later Nobel Laureate, Roger Sperry. This led on to work at Kings College, London, then to return home to the brand new Department of Psychiatry at the School of Medicine. Those were refreshing days, before sinking lids sank too far, and greater caution began to affect the course of NZ medical enterprise. In England I had worked with another young researcher, Dr Michael Craggs of University College, London, and Mike returned with me on an MRC Fellowship to New Zealand, to help me set up a laboratory and continue our work. My luck continued when I was asked to start the first graduate training programme in psychiatry. I was able to recruit a remarkable lot of young people, among whom were some who shared my love for fundamental research and became my colleagues and friends, including Rob Kydd, Alex Sergejew, and David Liley. My network of associates also expanded internationally, and so it has continued, apart from a period of absence in a personal research chair in Melbourne, until today, in my retirement.

In retrospect I can now see the work went through four phases.

1. The effect of motivational and alerting neurones on the EEG

The first phase began when I was a research fellow at Caltech, using unilateral electrical stimulation of motivational/reward pathways in the lateral hypothalamus and brain stem of “split-brain” cats, in which the great cerebral commissures were surgically divided. This showed that motivation systems in split-brain animals exert joint influence upon learning in both of the divided cerebral hemispheres, in contrast to the separation of cognitive functions produced by commissure division. This work carried on in London and after return to Auckland. We learnt something of the way brain stem pathways controlled the electrical activity of the cortex, but we could not identify separate signatures of activity associated with the diffuse motivational/alerting effects versus the cortically lateralised processes. Our frustrated efforts to do so showed that an adequate theory of the relationship to electrocortical activity to cortical information processing was lacking, and a decent theory was essential for progress.

So the part of the brain you stimulated, responsible for alerting and motivation, was located in the lower parts of the brain and affected all parts of the brain. What were the “signatures” of brain related activity you were looking for but couldn’t find? Was this electrical activity/EEG or something else?/

Our initial assumptions were pretty naïve. We recorded electrical signals directly off the animal’s brain, and measured their frequency content and the response to sensory stimuli. We hoped these signals would somehow be divisible into two classes that would correspond to the unified and separated aspects of cortical function in the split-brain animal, but we could not achieve this separation. Part of the problem was simply our (and everybody else’s) lack of understanding of the brain waves. Not where the signals were coming from, but the laws of wave motion that they obeyed. That led on to the second phase.

2. The development of a mathematical model of brain waves

The second phase, inspired by the frustration of the first, led on to a series of experiments to determine basic properties of electrocortical waves, so as to determine how a wave theory of the

brain’s activity might be formulated. This was when Rob Kydd, and later Alex Sergejew and David Liley, joined me. Mathematicians and engineers on Main Campus were very helpful offering advice, and we conducted a series of experiments that determined some of the mathematical properties of brain waves. In this work our able technicians John West and Nick Hawthorn played a vital part, as did our neurochemist colleague Gordon Lees. These gave some essential insights on how we could test a wave theory using computer simulations of large populations of cortical neurons.

So to develop a “signature” of brain activity you looked at the EEG and used concepts applied in mathematics and engineering to model the “brain waves” in the EEG? You then carried out a series of experiments to test the theory and then developed the mathematics further to show how cognitive processes were generated in the brain from sensory inputs and ongoing activity forming something like a bubbling soup of brain activity? Or is that the wrong image to apply?

“Bubbling soup” as an analogy is apt, but I’d better explain in a bit more detail. The work became a major enterprise. It led my colleagues and me to successful explanations of mechanisms for cortical pulse synchrony and oscillation, and of evoked potentials and the frequency content of the EEG. These results complemented the work of overseas groups led by Paul Nunez, by Walter Freeman, by Fernando Lopes da Silva and others, but also differed from the directions taken by them in certain important respects.

What emerged was a fusion of ideas and testing of alternate models until we arrived at a viable theoretical framework. The work has continued in Australia at the Department of Physics, Sydney University, where, with Professor Peter Robinson, Chris Rennie, and Evian Gordon, it later became the focus of an ARC Centre of Excellence under Peter’s auspices. We four shared the Eureka Prize for Interdisciplinary Research awarded by the Combined Royal Societies of Australia. Partly as a result of this work, it became possible to conceive of information transfer in the active cortex as a series of punctuated equilibria of signal exchange among cortical neurons – equilibria reached repeatedly, with sequential perturbations of the neural activity away from equilibrium thus forming a basis for cognitive sequences.

3. A model of visual perception

The third phase also began when I was in Melbourne, and arose from dissatisfaction with one aspect of the wave theories of brain function we were developing. It seemed to me these oversimplified the complex microscopic synaptic organisation of the cortex. A solution combining both aspects began when I was able to apply work undertaken with Clare Chapman on the origin of electrocortical pulse synchrony to produce a new theory of the regulation of embryonic cortical growth and the emergence of mature functional connections. This work reached somewhat different conclusions to those of the pioneers of the field; Hubel and Wiesel.

This third phase was then more specifically about perception, particularly visual perception. My understanding of the work of Hubel and Wiesel is that it focuses on the responses of single cells to particular inputs, such as a line in the visual field. What conclusions did your work reach that were different to these ideas?

The visual cortex is the best studied part of the cortex, so this provided the body of experimental data against which a theory could be developed. The classical theories of visual function from Hubel and Wiesel onward emphasised the tuning of inputs to the visual cortex from the eyes, as you say. Without contradicting that type of theory, our work stressed interaction among the neurons within the cortex – their contextual interactions. It turned out this could explain things that were apparently paradoxical in the earlier theories, and account for neuron interactions across the whole cortical surface. By this stage something like a coherent theory of cortical dynamics was beginning to emerge. Its overlap with certain aspects of thermodynamic theory was also becoming clearer, and linkage to developments elsewhere were increasingly apparent.

4. Relationship to the free energy principle of Friston and AI

Thus began the fourth phase. In about 2013 I made contact with Professor Karl Friston at the Wellcome Institute, UCL, Queen Square, London. Karl has advanced a major theory of all self-

organising systems called the Free Energy Principle that has gathered considerable attention in the past two decades. There is reason to believe that a strong general theory of brain function is now close. Our body of work contributes to this and parallels related developments in Artificial Intelligence (AI). Researchers in AI use simulations of large networks of highly simplified, somewhat unrealistic, neurones to replicate some of the cognitive functions of the human mind, and have enjoyed fabulous success so far. Work in Brain Dynamics on the other hand has favoured biological realism rather than emphasis on cognitive abstraction – but the two fields must fuse eventually. Paraphrasing a comment made about AI by one of its greatest founders, Geoffrey Hinton – If we can do that with a bad theory of neuronal function, what could we do with a good one? To return to my original motives for engaging in this work, the same might be said in regard to clinical psychiatry.

Could you elaborate a bit on the relationship to Friston’s theory?

Karl Friston has done something extraordinary. He has produced a conceptual unification of ideas ranging from the principle of least action, essential to basic physics, to the processes of learning in the brain as well as the operation of “deep learning” artificial networks used in AI. The EEG work, and the work I’ve been doing with Paul Bourke, although developed independently, has turned out to be a special case of Karl’s Free Energy Principle, and thus gains wider explanatory power. I mentioned above that the EEG theoretical work suggested connections with thermodynamics. That comparison is not incidental but crucial within the Free Energy Principle. Applying the Free Energy Principle with our understanding of the dynamics of brain waves, and other recent research on the embryology of the brain called the “Structural Model” we have now shown how systems of synaptic connections can emerge in paired subsystems, each ordered in roughly mirror symmetry to its partner. Each of a pair continues to interact with its partner during learning, to more closely approach exact mirror symmetry. This maximizes the mutual information in their exchanges, harmonizing them, so that each of the pair disrupts activity in the other to the least possible extent. The figure to be associated with this interview (see below) shows how these connections form. Harmonization of exchange between many such pairs, taking place along with exchanges with the outside world over the sensory and motor pathways, leads progressively to harmonization of the individual to the environment. The brain thus forms a “generative model”, minimizing the degree in which its ongoing function is disrupted by “surprise” – that is, the arrival of unanticipated sensations. So, I hope you can see why I suggested that a general model of brain function may be close.

I understand he (Friston) has related his work to some of the phenomena people with schizophrenia experience? Also could you speculate on what all of this might mean for clinical psychiatry. Will we eventually be able to apply this to diagnose conditions or monitor treatment?

Extensions of this work have led to analysis of EEG and brain scan data in psychiatric settings, aimed to increase precision and understanding of abnormal findings. This has been the goal all along. Evian Gordon, one of my colleagues while in Australia has taken this work onward by creating a database of recordings from patients with major mental illnesses and matched control subjects, with the object of being able to increase diagnostic precision. This has been achieved in some circumstances, but has also made plain how complex this task is. Artificial Intelligence is needed in the analysis of the data, and the size of the normative database must be very large indeed. But it can be done.

The formal Free Energy Principle arose first in the context of statistical analysis of brain scans in psychiatric research, and thus has been aimed at practical psychiatric outcomes since its inception. The generality of the principle enables linkage between theories, say, of the brain and neurons, to otherwise apparently disparate subjects – like psychiatric mental phenomenology – leading on to what has been called “computational psychiatry”. The object is to describe the abnormalities of mental illnesses as far as possible, as derangements of Brain Dynamics. It’s early days, but already there are advanced ways of analysing scans and EEG in psychiatric context. If these became standard parts of clinical practice they would revolutionize diagnostic formulation and we could expect that they would then guide the pathway of management. But sadly, they remain too complex and costly to be practicable for widespread application. One must accept that is generally the case with any radical advance in its early stages. We must wait and see.

Can you tell us more about what impact receiving support from the Foundation has had on your career or future research opportunities?

As I implied at the beginning of this interview, my career has been something of a Rake’s Progress. I have had a lot of luck and excellent support. This includes research fellowships for myself and my colleagues, and grant funding from Caltech, MRC (UK), ARC (Aust), NH&MRC (Aust), MHRC (UK), MRC and later HRC(NZ) and AMRF, including a very large grant through the Pratt Foundation of Australia when in Melbourne. However, this work has always been controversial and funding has been frequently declined. Refusal on grounds of caution is of course right and proper and to be expected – but when a project is as long-term as this has been, a funding drought can result in the loss of critical and valuable research workers and technical staff. It is on such occasions the Foundation has come to my aid several times, with relatively small, but absolutely essential funding relief. I will be forever grateful.

How would you describe the significance of support from Whau MentalHealth Research Foundation for researchers in mental health?

In my opinion the most important role of the Foundation is to seed early research by younger researchers (or recently inspired working clinicians) to get a climate of research-driven work established. Quite apart from its intrinsic value, the value for morale and recruitment within MH services cannot be over emphasised, and I wish there was more of it – much more. For the services themselves to be effective a critical mass of well-informed leaders must be sustained, and research training encourages rational initiative in a way like no other.

As I have said above, I want to point out a secondary role – the bridging of finance so that long-term projects with scientific depth can be sustained. The Foundation saved my work and my career. I hope it will save others.

Where can we find publications of your work?

My publications can be found at https://scholar.google.com/citations?hl=en&user=FQUMolYAAAAJ

These publications acknowledge the Foundation in numerous instances. The most recent is

at https://academic.oup.com/cercor/article/34/10/bhae416/7848491

Left: Theoretical reconstruction of the disposition of cells and synapses in a surface-oblique view of a single cortical column. Large coloured neurons represent superficial patch cells. Black smaller cells are local short-axon excitatory cells in layers 2/3 and 5/6. White cells are those of layer 4. Small coloured spheres represent synapses projected from patch cells of the same colour.

Right: A set of seven adjacent cortical columns. It can be seen that each of these columnar organizations forms an approximate mirror of its surrounding neighbours. The pattern of connections corresponds to that in real neurons. The mirror arrangement enables

learning to evolve toward an optimum (see text)